CateDevineWriter

IF WE are what we eat, then what was Queen Victoria? This brilliant first book by the food historian and broadcaster Annie Gray (above) wastes no time in telling us. The waspishness of the title segues pleasurably to the gossipy opening line stating that “in July 2015 a pair of extraordinarily large bloomers were auctioned in Wiltshire”, and if you are tempted to flick to the photographs a few pages in, as I was, her 50-inch-waist mourning dress [see below] defies any attempt to deny the fact that food was central to the British monarch not only during her 63-year reign but also before she was crowned at the age of 18. Basically, it appears her obsession with food was off the scale. (Continues ...)

Black silk and net gown worn by Victoria in the 1890s © Fashion Museum, Bath and North East Somerset Council, UK/Bridgeman Images.

(Continued.) Victoria was a product of her personal environment, but she also presided over the seismic culinary changes that took place in 19th century Britain. So, rather like a well-iced cake, this book is two things: on the outside, a jaw-dropping record of the diminutive monarch’s personal eating habits, and underneath a fascinating, and surely definitive, chronicle of the evolution of British food.

Victoria favoured French menus and French chefs. The first royal dinner of her reign, upon moving to Buckingham Palace in 1837, offered guests two kinds of soup, four choices of fish, beef steaks, braised capon, roast lamb and baby chickens with tongue; lamb cutlets, fillets of sole, four different chicken dishes, sweetbreads, pates a la reine; roast quails and capons, German sausage and souffle omelette. Then entremets of lobster salad, fricassee with jelly, gardens peas and artichokes. The sweets consisted of fruit macedoine, wine jelly raspberry cream, vanilla cream, biscuits, cherry vol-au-vent, a Chantilly turban, German cake, sugar baskets and nougat. There was the addition of a sideboard with a sirloin of beef and a chine of mutton.

This was only the beginning. As time went on, “a great deal of eating went on at the Palace”. Victoria had a lifelong penchant for mutton chops, creamy sweets and sauces, and developed a taste for whisky in her claret – despite being plagued with chronic indigestion. She gained a reputation for eating all day, being a party animal “most alive at 3am”, and became bloated and heavy.

The arrival of the frugal Albert, for whom food was but a means to an end, put on the brakes, but not for long.

The sheer volume of food prepared for the royal family, royal household, upstairs and downstairs staff and hangers-on not to mention for royal banquets and visiting dignitaries, defies belief – and puts the focus on the cooks who had to produce it in royal kitchens that were variously badly ventilated and poorly plumbed. This was “mass catering on a factory scale”. In March 1865 alone, 8257 people ate food cooked by the royal chefs.

Preparing it was not only time-consuming, it was dangerous. Heart disease from a lifetime of roasting meat at open fires; carbon monoxide poisoning from charcoal stoves; fallen arches due to hard stone floors, joint problems from sheer physical hard graft; and severe burns (or worse) from clothes catching fire were just some of the risks.

The evolution of ‘a la Francaise’ service to ‘a la Russe’ is particularly well described. In the former, platters of spectacularly presented food were laid out on the communal table according to meticulously drawn table plans, to be served by footmen – or for guests to help themselves. This apparent communality masked social challenge. Diners “had to be aware of each other, be able to share, and not look greedy”. By contrast, ‘a la Russe’ meant each course was served separately by waiters and the choice was reduced significantly. With it came the written menu, and the banishment of all food from the table, as it was portioned up in the kitchen. Unsurprisingly, Victoria resisted it with all her might for as long as she could.

Gray’s oeuvre is deeply satisfying, yet so rich in detail that I found it only digestible when consumed in small chunks. It suggests voracious and, one imagines, time-consuming research. What saves it from being overly academic is that from the outset, her tone is lively, her pace jaunty and – apart from the odd interjection such as that describing Victoria’s cast of relatives as “hideous” – her opinions neutral. There is little malice or judgement, even in the face of the most stomach-churning revelations (such as Victoria’s erratic bowel habits). If anything, there’s a whiff of empathy.

Over-eating and yo-yo dieting as a five-foot-one-inch tall adult had its roots in a childhood in which Victoria was fed nursery food until her early teens, consuming it alone, only to be berated by her adored uncle Leopold for eating too much and too fast. Born “as plump as a partridge” to the domineering Duchess of Kent, she finally asserted control as a teenager, fasting and losing stones in the process. When thrown into widowhood early, she comfort ate for the rest of her life, only losing her appetite completely in the weeks before her death.

So perhaps the title of this book is not as simple as it might suggest. Gray’s candour throughout is refreshing, even if it does leave one feeling rather bilious.

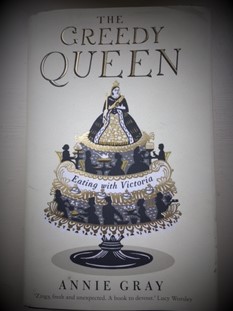

The Greedy Queen: Eating with Victoria, by Dr Annie Gray, is published by Profile Books at £16.99.

* This article was first published in The Herald.